Editor's Note: Take a look at our featured best practice, Business Case Development Framework (32-slide PowerPoint presentation). The Business Case is an instrumental tool in both justifying a project (requiring a capital budgeting decision), as well as measuring the project's success. The Business Case model typically takes the form of an Excel spreadsheet and quantifies the financial components of the project, [read more]

Interview with Author and Hedge Fund Manager Jeff Gramm

* * * *

Editor’s Note: This is an interview originally conducted by Nitiin A. Khandkar of Beyond Quant InvestTraining and published here.

This author has also published several financial models on Flevy, including the World’s First Research Report-cum-Financial Model and a BSE Ltd. (Bombay Stock Exchange) Financial Model.

* * * *

Our guest today, is Jeff Gramm, who runs Bandera Partners, a long-oriented, value-driven hedge fund based in New York City, USA and also teaches value investing at Columbia Business School. Jeff authored the highly acclaimed “Dear Chairman”, a book focused on Shareholder Activism, which shares key insights into activism initiatives by leading investors such as Benjamin Graham, Warren Buffett, Carl Icahn, Ross Perot and Daniel Loeb.

“Dear Chairman” has been praised by luminaries including Warren Buffett, Carol Loomis, former SEC chairman Arthur Levitt, former Fed chairman Alan Greenspan, FedEx CEO Fred Smith, and Charles Schwab, chairman of the Charles Schwab Corporation.

The interview is in podcast and transcript formats.

Podcast of Interview with Jeff Gramm

Transcript of Interview with Jeff Gramm

1. Hi Jeff, how are you? Could you please share your professional background, something about your hedge fund, and how you decided to write a book on Shareholder Activism?

As for deciding to write the book: I started teaching investing at Columbia Business School in 2011, and the students were always asking for book recommendations. Instead of recommending books, I’d give them articles, speeches, and I gave them these 13D shareholder activist letters, which I thought were useful for teaching purposes. In those letters the activists often spell out their investment thesis, why they like the stock, and they also explain the reason why they think the company is under-managed. After a few years of this, I figured there must be a book collecting those activist shareholder letters, and when I couldn’t find one, I thought, “well I can do that myself.” From there, it really evolved into the narrative history of activism that became “Dear Chairman”. I never really had the time to do it, as I have a full-time job as a fund manager. But I was requesting these original letters from shareholder activists, and every time I got one, it inspired me to keep pursuing the idea. One day I came to work, and Warren Buffett had sent me a copy of his 1964 letter to American Express, and that lit enough of a fire under me to force me to finish the book.

2. Nice to hear that, Jeff. What in your view gave rise to shareholder activism in the US? The Ben Graham versus Northern Pipeline case dating back to 1926, as documented in your book, is probably the first shareholder activism case in recent times, in the US. However, shareholder activism seems to have taken off only after the 1970s or 1980s. What could’ve caused the hiatus in activism in the intervening period?

Jeff: Well, as long as there have been public companies, there have been active, engaged owners looking out for their own interests. The very first public company, the Dutch East India Company was chartered in 1602 and saw various uprisings from unhappy shareholders. In America, there were active investors in very early banks, toll roads and railroads. So, activism didn’t begin with Benjamin Graham. What makes him interesting and special is that Graham was among the first professional investors with underlying clients to employ shareholder activism as part of his investment strategy.

We all think of the 1980s as the start of activism and corporate raiding, but that’s not true. There was a period of robust shareholder activism in the 1950s called the Proxyteer movement. The second chapter of my book is about a famous battle over control of the New York Central railroad. As you can see in my book, much of the history of shareholder activist interventions is driven by the evolution of the investor base of public companies. These activists get all the attention and headlines, but the voting shareholders behind the scenes play a huge role in my book. And they’re key characters in my book.

In Benjamin Graham’s time, most public companies had concentrated shareholder bases comprised of founders and strategic investors. When he targeted Northern Pipeline company, for instance, the Rockefeller Foundation owned about 25% of the company, and Graham spent considerable energy appealing directly to them. By the Proxyteer era, share ownership in the US had diffused into the hands of individual investors. Proxy campaigns in this period were like political campaigns – newspaper advertisements, appearances on TV news shows, that kind of stuff. The Proxyteer period did not last that long.

Starting in the 1960s, share ownership began to re-concentrate in the United States, this time into the hands of fiduciary investors like pension funds and mutual funds. A shareholder activist today has a different job – he/she needs to appeal to those sophisticated institutional investors as opposed to individual holders. That’s why hedge fund activists of today are very smooth, presentable and quite politically adept.

3. Okay, these are quite interesting perspectives, Jeff. All the activists covered in your book are quite influential. Which of the activism cases covered in your book, is the most significant in your view, and caused the biggest change, in favor of minority shareholders?

Jeff: Well, to me, Ross Perot’s intervention at General Motors ($GM) was the most significant. This is also the best chapter in the book, it’s the most fun chapter. This was the mid-1980s, and corporate governance in the US at that

point was bleak. Passive shareholders were exploited by corporate raiders, and hostile raids, as well as by corporate management teams which were paying greenmail to activists or executing their own management buyouts. Big institutional investors were very touchy after several years of mistreatment, and then the Ross Perot saga happened.

Ross Perot was a legendary businessman who sold his company to GM, and then joined the board as the largest shareholder. Investors were thrilled with the idea of Ross Perot injecting some life into GM’s board. Instead, what happened is, he instantly clashed with CEO Roger Smith, and GM eventually paid Perot $700 million to get him off the board. Institutional investors who had seen GM begin to falter, had seen Toyota and Honda emerge as formidable threats, were shocked that a struggling company like GM would use so much precious capital just to weaken its board of directors. One large pension fund manager said, “We’ve been asleep at the switch.” Those big pension funds revolted against GM and a bunch of other public companies in the 1980s. Hedge fund activism as we know it today is possible because of this big awakening of large, passive, institutional investors. The hedge funds get the attention, but in order to make their activism work, they have to appeal to the big pension funds. Before Ross Perot, big pension funds were extremely trusting of incumbent boards and management and that began to change in the 1980s. Perot was a big turning point.

4. Why do hedge fund investors in particular, engage in activism, rather than simply exiting the stock? Are mutual funds too known to be as aggressive in activism?

Jeff: Activism can be a really useful tool to unlock value at public companies. Carl Icahn’s early career as an activist showed how interventions at undervalued companies often resulted in quick, bonanza results. The bargains are fewer and farther between today, but in a way, this encourages more activism. It’s a very competitive world. Hedge funds are trying their best to get an edge that allows them to outperform. For many funds, actively engaging with public companies, rather than just exiting the stock when they struggle, is a core strategy.

Mutual funds are not known to be as aggressive, but it’s not unheard of to see mutual funds lead activist interventions. It does happen a fair bit, particularly the older, established value mutual funds.

Most of the value investors I work with understand that activism is a valuable tool that comes in handy when dealing with underperforming companies. If we simply exited every stock that did not perform up to our expectations, I think all of our returns would suffer. There are just these inherent structural problems with how public companies work, and with how incentives are misaligned between the CEO, the board of directors and the outside shareholders. Even well-operated companies, are rarely managed perfectly. The very first chapter in my book is a classic example, in which Benjamin Graham intervenes at Northern Pipeline company to force them to distribute excess cash. Lots of public companies allocate capital extremely poorly, and it would be a shame to just exit our position in a good, cash-generating company because of their poor capital allocation. Why not try to get involved and make a case for improving that aspect of the business?

5. Fair enough, Jeff. That sounds like the right argument in favor of activism. Strategic investors add value to the money they invest, by utilizing their contacts, experience, and knowledge of market, with a view to brightening the investee’s prospects. As opposed to strategic investors, hedge funds or retail investors are primarily financial investors. Strategic investors are capable of actually running the business. In contrast, a hedge fund can never probably run the business in which it has invested, with the same acumen or expertise as the founders/managers may have. I’d say that it is the strategic investors who have the first right to be activist shareholders. Would you concur?

Jeff: Well, I’m not sure. You have to remember that like we just talked about: a lot of activism, perhaps even the majority of it, focuses on capital allocation rather than strategic direction or operations. And that makes a lot of sense, because investors are supposed to be experts in allocation, while lots of great operators are not necessarily skilled at deploying capital.

Secondly, even if a hedge fund manager is not an industry expert, that does not mean he or she cannot lead a successful intervention by adding qualified industry experts to a company’s board of directors. This can be the best of both worlds – where you have qualified investors with experience, which is a strategic value-add for the company that also really puts the shareholders first. But you do make a great point. I should also point out that all these lines are blurring in the industry. I’ve seen plenty of hedge funds that advertise their experience as strategic, private equity investors. You just see a lot more operationally focused hedge fund activism where they are not uninformed. But I think on a more fundamental level, I’m not sure anyone has the first right, or doesn’t have the right to be an activist shareholder if they own shares and are not happy with performance. What really determines success will be the quality of their ideas and the activist’s ability to persuade the rest of the shareholder base that those ideas merit support.

6. The overt intent behind activism is to increase returns for shareholders. However, which of the broad types of activism, viz., corporate governance, maximizing shareholder value, board control / representation / removing directors, is more prevalent, as per your research? Are activists focused more on maximizing shareholder value and board control?

Jeff: Activist investors are, at their core, economic actors out to make a profit for themselves. So, their main objective is for their investment to increase in value, it’s not just to win control of the board for the sake of control. Lots of proxy fights “fail” in the sense that the activist does not win board representation, but at the same time, they “succeed” when management co-opts their arguments to win the support of shareholders. You see this dynamic quite often, and it often has positive effect on the stock. One that comes to mind is Sardar Biglari’s fight against Cracker Barrel ($CBRL). Biglari ran multiple campaigns to unseat Cracker Barrel’s board. He never won; he lost all the proxy fights – but he really got managemen

t to focus on shareholders and begin to cut out some of the bloat in that business. Despite the fact that he technically “lost” the proxy fights, the stock more than doubled. So, what’s important is that he made a huge profit on his shares of Cracker Barrel. Shareholder activism that is purely motivated by governance concerns rather than actual investor profits has historically been pretty insignificant.

7. Jeff, of late, activism seems to be on the rise in Corporate America. As per FactSet Insight, the number of activist campaigns went up from 221 in 2010, to 377 in 2015 before tapering off to 316 in 2016. Since 2010, the Dow Jones Industrial Average has almost doubled. Is the rising activism led by investors who feel they’ve not been able to participate in the stock market rally?

Jeff: That’s an interesting question. Historically speaking, you often will see blooms of activism during long bull markets. You saw this in the 1950s as well as in the 1980s. I don’t think it’s led by investors who feel left out, I think in some ways it’s fed by typical animal spirits and bullishness on corporate prospects, as well as importantly, the financial health of those activists. If the activists have some success at the beginning of the bull market, they build up a big war chest as the market progresses. The long bull market in the 1950s really deepened the pockets of a lot of the early Proxyteers, and that allowed them to go after newer and bigger targets in the late 1950s. This decline in the activism that we’re seeing now – the recent tapering in activism, I wonder if it has more to do with hedge funds under-performing and feeling less buoyant, which would support that point. Beginning in about 2015 when you saw that peak, a lot of the major activists began to suffer pretty terrible performance and I’m sure that influenced the overall number of proxy fights. This all speaks to the inefficiencies of the stock market. In an ideal world, activism would ebb and flow based purely on opportunities in the market, when stocks are cheap, or when there happens to be some kind of bloom in bad governance, but that’s not how things always work. So, I think it has less to do with investors feeling left out. The recent decline has more to do with a little bit pain on the part of these activists.

8. Of the activist campaigns in 2016, as much as 75% was against companies with less than a billion dollars in market capitalization. Why do you think activists target small companies only, while letting the big fish off the hook?

Jeff: Well, that’s a good question too, and I thought about that some. On the one hand, you have so many more small companies, a lot of it just has to do with the numbers. With so many small listed companies, that it naturally follows that you see more activist campaigns in that segment of the market. That being the case, I do think that corporate governance and the quality of corporate directors improves as companies get larger. The longer I’ve been doing this, the more I believe that, in general, larger companies tend to have higher-caliber directors, and that means better governance. Of course, this doesn’t prevent corporate governance disasters from happening, and you still have fundamental structural problems that we talked about, that make the job of being a director very hard.

But in many very small companies, it goes beyond structural problems – to the fact that a lot of them are just horrifically governed, and you do see things that indicate really bad behavior. Sometimes you see blatant self-dealing, and the kind of promotional scams that you don’t see as often at larger companies. And of course, it’s easier to be an activist in a very small company, because it takes a lot less capital to establish a material ownership stake. It’s a lot easier to be a successful activist if you have a material position in the underlying company. With very small companies, there’s just a lot more investors out there that have the means to do that. With a really big company, like if you’re going to activist on Microsoft ($MSFT), it’s going to be really hard to be successful and to have any credibility, it would help to have a least a material position and you know, who has the money to have a material position in a company like Microsoft?

9. Yes, absolutely, Jeff. Does activism take place in poorly managed companies, or even in companies generating decent RoE and dividends? If yes, why? Whole Foods Market ($WFM) is currently in the crosshairs of activist hedge fund Jana Partners which took a nearly 9% stake in the company and suggested it should consider putting itself up for sale. Even Amazon was reportedly interested in acquiring $WFM. What are your views on this? Do you think $WFM is a fit case for a sale?

Jeff: You raise a good point here – we don’t only find shareholder activism in woefully underperforming companies. Even Apple ($AAPL) was targeted by two prominent activists, Carl Icahn and David Einhorn, during a period when the company delivered just stunning financial performance. I think the most common feature among activist-targeted companies is a poor performing stock price. If the chart of the stock looks like a descending line, that bodes well for an activist being able to tap into the discontent among the shareholder base. But there are some exceptions. Companies that are performing well, like Apple, can still get targeted for their capital allocation choices. We’re seeing this right now at General Motors ($GM), where David Einhorn is calling for a restructuring of the share classes and Mohnish Pabrai is taking an opposite point of view, and saying that he’d be happy to see them scrap the dividend altogether. You know, GM has not performed better, in recent memory. It’s probably been since the sixties since they’ve been doing this great. So, you’ll still see activism even in companies that are doing well.

As for Whole Foods, I haven’t closely followed the Whole Foods drama, but it is an interesting case. Whole Foods is a fine business, but the competition in the US has really caught up to it. If you go to any of its major markets, there are lots of equivalents of Whole Foods, often with more competitive prices. So, I’ve always been a little bit afraid of the stock because I thought they were over-earning, that those operating margins needed to come down. Many of their strategic initiatives haven’t worked out, and shareholders are concerned that the clock is ticking and that management is squandering a wonderful brand and reputation. But I’m not close enough to the situation to know how dire things have gotten, or whether it makes sense for shareholders to try to find a buyer for the company.

10. Ross Perot once said, “The activist is not the man who says the river is dirty. The activist is the man who cleans up the river”. Do you think activism is generally positive, and in the interest of all stakeholders? Do you think the rising activism has the potential to even disrupt normal business operations of companies which face such activism?

Jeff: It’s interesting that you use the word “stakeholders”. In the US, the word “stakeholders” when it is applied to public companies, usually means the employees, the community, as well as shareholders. Clearly, shareholder activism in the US, and public company governance in general, has forsaken the community. Companies move all the time just for economic reasons. We just saw this when Jamba Juice ($JMBA) moved [from Bay Area] to Texas. GE is leaving Connecticut where it’s been forever. When shareholder activists get involved, they’ll often cut local charitable spending, as we saw with DuPont ($DD). They were targeted by shareholder activists, and they received a lot of criticism for how much they spent on charitable causes in their hometown, Wilmington. It’s not as black and white with labor, but often activism drives the kind of “efficiencies” that pressure labor costs.

All of this said, while I do think there are cases of bad activism – and there’s a chapter in my book, on BKF Capital ($BKFG), that really shows shareholder activism at its worst, when misguided shareholder activists destroy the company – I do believe that the pervasive threat of activism that we have in today’s markets is a positive force that puts some necessary accountability in the system. If you’re on a corporate board today, you know that shareholders are looking over your shoulders. I think that is a very good thing for the system. We’ll continue to see cases where activism goes wrong, where shareholders have wrong ideas for the long-term direction of the company. But the fact that they have a voice and the fact that the directors know that they have to answer the shareholders, that’s incredibly important. I think if that’s missing, the system can really stagnate.

11. There are advocates and opponents of activism. Usually, activists are interested in opposing those key decisions of the management, which they feel are detrimental to the interests of minority shareholders. But are activists really looking at protecting other minority shareholders, or concerned primarily with their own interests?

Jeff: We talked about this a little bit earlier. One of the key themes in my book is that activists are concerned primarily with their own interests. The system works best when their interests are aligned with all other shareholders, but when that is not the case, look out!

There are several examples in my book of activists who use pro-shareholder rhetoric to get control of the board, but then once they are in charge, they happily screw the other holders over. We always must remember that shareholder activism is not a broad movement to make small, incremental improvements in public company governance. It is a powerful tool, employed by opportunistic investors, to overhaul specific boards of directors. When activist investors are doing this, they’re looking out for their own interests and profits. When they are aligned with other shareholders, that is great. And that’s usually how it works. Big passive institutions play a big role in this, and it hurts your credibility with them if you screw shareholders. But when activists are not aligned with other shareholders, it can be problematic. Historically, when activist investors have gained total control of public companies, they have not always acted appropriately to minority investors.

You saw this across a lot of different markets. You saw this in the 50s with the Proxyteers, in the 60s with the Conglomerators and the 80s with the Corporate Raiders. We see it with the hedge fund people too. We talked a bit earlier about Sardar Biglari earlier. I have tremendous respect for him as an operator, but after he got control of Steak n’ Shake, which is a restaurant chain, he began to pay himself enormous sums of money. I just saw yesterday that he made $32.5mm last year from Steak n’ Shake, which he has renamed Biglari Holdings ($BH). That’s a tremendous amount of money for a small company CEO. I saw someone tweeted that it’s more than the CEOs of McDonalds ($MCD) and Chipotle ($CMG) combined!

Alright. Yes, that’s very unfortunate when small company CEOs start paying themselves salaries which are simply not justifiable.

Jeff: Yeah, once they have control of companies, there’s a lot that the management teams can do to enrich themselves, if they want to.

12. Is activism the prerogative of only institutional investors? Should retail, individual investors too come together and actively oppose such decisions of the management or even the hedge funds, which they strongly believe are not aligned their interests? Along with hedge funds, retail investors apparently played a role in DuPont’s defeat of Nelson Peltz of Trian Fund Management in the proxy fight in 2015. What are your views on that particular conflict involving management, hedge funds and activist investors?

Jeff: That’s a great question. As much as I love democracy, and I love the idea of mom and pop investors wisely voting their proxies, it’s very hard for retail investors to have their voice heard. The stock market is dominated by huge institutional investors like Vanguard, Blackrock, CalPERS, and TIAA-CREF, who hold a very large percentage of public company shares. It’s pretty rare that proxy fights are so close, like in Trian-DuPont, where retail votes swing the outcome. But that said, if you are not happy with a management team or with an activist shareholder trying to intervene, it’s better to say something than nothing. But you are right – in a sense the market today is characterized by these huge passive institutions being the arbiters in activist disputes. They have a symbiotic relationship with the hedge funds – often they even recruit the hedge funds into intervening – it kind of leaves out the little guy. And there’s not much of a chance for smaller individual investors to have a say.

The fate of DuPont is pretty telling. It was a close vote, and the individual investors, many of whom lived in Delaware, where DuPont was based, and owned the stock for generations, they played a big role in turning the vote in management’s favor. But it turned out to be an empty victory. Over time, even though it lost that particular proxy fight, Trian basically got everything it wanted, both leading up to the proxy fight, and after the proxy fight. DuPont spun off its chemicals business, replaced its CEO, and the new CEO immediately promoted and then achieved a merger with its rival, Dow. So, the individual investors, many of whom were voting their shares in the interest of maintaining the normalcy and a status quo for DuPont in Delaware, they won the proxy battle, but they ultimately lost the war, the big guys’ war.

13. As per Brunswick Group research, retail investors think the business environment in corporate America is ripe f

or activism, with 77% of retail investors indicating that US companies are holding more cash than ever on their balance sheets and should be returning profits through dividend payments. Do you agree with this?

Jeff: That’s a complicated issue. As we discussed earlier, a lot of activism is focused on poor capital allocation at public companies, and many of the battles in my book, including the first one with Benjamin Graham, are about returning excess cash to shareholders, as opposed to allowing it to sit around. That said, I don’t necessarily think that most companies should pay more dividends. Companies face hard choices with capital allocation, they do have lot of options – they can pay dividends, they can pursue M&A opportunities, they can repurchase shares, and, of course, they can deploy capital into their business. Well, I love it when my companies reinvest their cash into their business, if they can achieve good rates of return. If they can’t, I love seeing opportunistic repurchases if the stock is cheap. And where there are businesses I own that can profitably grow their business through M&A, I’d prefer they build cash to pursue acquisitions rather than return it. One of my largest investments, Star Gas Partners, is a heating oil distributor in the North East, that can really add value for shareholders by acquiring other dealers. I would rather see them do that, than pay lot of dividend; it’s a bit complicated.

We also must remember that lots of this cash that you read about in the papers, or the media talks about is held overseas. I’m involved in one company where a lot of our cash is in Canada, and we’d have to pay taxes on it to repatriate the money. So, I guess this is all a long-winded way of saying, I often see dividends as a last resort, and often it’s less easy to distribute cash than it might look like from the 10-K and balance sheet.

14. Do you think legislation as regards protection of rights of minority shareholders, or monitoring related-party transactions could be made even more stringent, partly obviating the need for activism?

Jeff: No, I can’t think of any obvious regulatory fixes that would be a win-win for shareholders. If a public company management team and board has extremely bad intentions, there are plenty ways for it to enrich itself that would be essentially impossible to regulate away. The business world is a messy place with a lot of conflicts of interest, but I tend to favor freer markets. I think the business judgment rule, which gives managers a lot of leeway in their decision-making, is a good thing. I think over-regulating public company governance will just result in fewer companies going public, and fewer public companies taking the kind of risks they need to take to compete in the market.

One of the interesting themes in my book, that comes across over and over again, is that there really are no best practices in corporate governance. There’s no list of rules that will make a board of directors bad or good. Just last year, Jamie Dimon, Warren Buffett and a bunch of other big-shots in the financial world tried to create a list of best practices and they called it common-sense principles for good governance. The document is interesting, and very much worth reading, but I think it speaks volumes about how hard it is to conjure up truly “best practices” for corporate governance in the traditional sense. Ultimately, a director is good is he’s engaged, informed and checked-in. Putting energy and effort into the job is the best practice I can think of. Any form of checklist-style assessment of directors tends to fall short, and many of the standards we focus on, like director independence, for example, are not perfect solutions.

I obviously think corporations need to be carefully regulated, but I think a lot of legislation focused on protecting shareholders could end up with unintended negative consequences.

15. The advent of activist investors has also led to the rise of investment bankers who are setting up special activism-focused units, and advisors, who seek a pie of the growing business. Do you think such advisors could also add fuel to the fire, simply to further their own interests?

Jeff: That’s a great question, and the answer, in my opinion, is that history has already shown this to be true. Some of the biggest figures in the evolution of shareholder activism have been the advisors, from Michael Milken to Joe Flom to Marty Lipton. Nobody added more fuel to the fire than Michael Milken. It was in his interest in the 1980s to promote corporate raiding, which he could fund with his junk bond sales to his vast network of customers. He had more demand for bonds than supply, and this created a huge liquidity boom for corporate raiders like Nelson Peltz, Ron Perelman and Carl Icahn. All those guys made their name because of Michael Milken. Marty Lipton, was another advisor who shaped the industry. But he did it for the other side, as a corporate defense specialist. He invented the poison pill and various other mechanisms for slowing down activist investors and hostile raids. So, advisors have played a huge role in how the market for corporate control has evolved over time.

16. Have you been involved in any activism in your own hedge fund, or have joined hands with other hedge funds for activism? If yes, what kind of results were you able to achieve?

Jeff: Yeah, we’ve done a fair bit of activism. When we engage in activism, it is usually a defensive measure involving a company that we already have a big position in. It’s pretty rare that we’ll activize from the start. Right now, we are on two boards – I serve on the Tandy Leather ($TLF) board, and my partner Greg is a director at a company called Pico Holdings ($PICO). I’m very happy with our performance and our results as directors, though it’s important to note that sometimes the stock performance isn’t necessarily correlated to our job performance as directors.

I’ve finished three directorships – Peerless ($PRLS), Morgan’s Foods ($MRFD), and Ambassadors Group ($EPAX). Peerless and Morgan’s Foods saw excellent gains for shareholders. Peerless returned a huge amount of capital to shareholders through a self-tender. Morgan’s Foods was acquired at a wonderful price by a strategic buyer. Ambassadors Group was a total disaster where we ended up liquidating the company and taking a huge loss. But I’m actually prouder of my service as a director at Ambassador than I am at either Peerless or Morgan’s. Pulling the plug on Ambassadors Group’s operating business was a brutal, difficult decision, we had to lay off hundreds of employees and it was a hard thing to do. But I think we saved a lot of shareholder capital by doing it, and I think a lot of boards would not have gone through with that.

17. Coming to my last question today, Jeff, activism is in a nascent stage in India, and has only taken root over the last decade or so. Remarkably, minority investors are increasingly taking an interest in activism, opposing decisions of the management which they believe are against the former’s interests. With most Indian companies being controlled primarily by founders, who typically hold significant stakes of 30%-60%, what would be your take on the rise in activism in India, going ahead?

Jeff: That’s a real challenge – it’s very hard to go active on a controlled entity. In some sense, it’s an opportunity for

activism there, because you see lots of extremely bad performance at controlled entities and so the stocks will be extremely cheap and you know if you can improve the management, you’ll get a great return on the stock. But it’s a very hard road. You can try to persuade the founders with your brilliant strategic ideas, but this is often very, very difficult. Founders rarely want to hear from minority shareholders. Outside of that, you can resort to trying to publicly shame them, find ways to get them out of office, if they’ve done bad deeds. But that’s a tough game too, and it makes you a lot of enemies!

It reminds me of hedge fund activism in the 90s and early 2000s when they really played the shame game. There’s a chapter in my book that’s about these hedge fund activists predominantly going after controlled entities. There’s a guy in the book named Bob Chapman who I talk about a lot, who would often target companies where control was locked up and he, just through force of will, and being a nuisance for them and trying to embarrass them, actually achieved pretty great results.

It’s been interesting to watch activism in other countries. You would think the biggest factors in activism would be legal and regulatory ones – like how shareholder-friendly securities laws are. But really it often boils down to the culture. Some cultures seem conducive to activism, like Australia, I think China will emerge as a market that’s like that. And there are others like Korea, for example, that aren’t. Korea has historically been extremely harsh on foreign capital trying to meddle.

Britain is interesting because the laws are very shareholder friendly, but it just isn’t a very activism-friendly place. I was involved in an activist situation there, where all the dissidents were foreign overseas funds, and all of the local institutional funds supported the management. I think the dissidents were right in that case. It’s interesting how the culture has a bigger impact than the regulatory environment.

Well, great insights, Jeff!

Jeff: Thank you so much for having me. This has been a blast!

All your views and insights into activism, and the numerous activism case studies you shared, are a superb value-add for my audience. Thanks so much, and it was nice to have you here today. Have a nice day!

Jeff: Thanks, it was great to be here.

Do You Want to Implement Business Best Practices?

You can download in-depth presentations on Financial Modeling and 100s of management topics from the FlevyPro Library. FlevyPro is trusted and utilized by 1000s of management consultants and corporate executives.

For even more best practices available on Flevy, have a look at our top 100 lists:

- Top 100 in Strategy & Transformation

- Top 100 in Digital Transformation

- Top 100 in Operational Excellence

- Top 100 in Organization & Change

- Top 100 Management Consulting Frameworks

These best practices are of the same as those leveraged by top-tier management consulting firms, like McKinsey, BCG, Bain, and Accenture. Improve the growth and efficiency of your organization by utilizing these best practice frameworks, templates, and tools. Most were developed by seasoned executives and consultants with over 20+ years of experience.

Readers of This Article Are Interested in These Resources

|

|

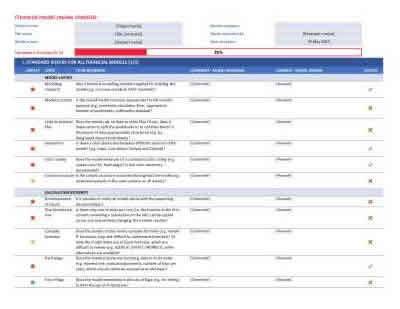

Excel workbook

|

|

96-slide PowerPoint presentation

| |||

About Nitiin A. Khandkar

Nitiin A. Khandkar is a Chartered Accountant and the Founder of Beyond Quant InvestTraining, an investment training venture based in Thané (Mumbai) India. Prior to founding Beyond Quant InvestTraining, he has had a multi-faceted career as a sell-side equity research analyst in India, a buy-side analyst and portfolio manager in US equities. He was Head of Institutional Equity Research desks, with a couple of sell-side firms in India. In the past, Nitiin has arranged one-on-one institutional investor road-shows for a few India-listed companies. He has also marketed Indian IPOs to foreign institutional investors and private equity investors. Nitiin was the winner of the Best IPO Analyst Award for 2009 by television channel Zee Business. He has worked in India and overseas. Nitiin remains passionate about Value Investing, and likes to read books on the topics. He continues to write on investing themes, and builds financial models on Indian companies. Nitiin also advises Indian start-ups/corporates on raising funds from VCs/PEs. Nitiin can be reached at founder@bqinvesttraining.com and nitin.k.ier@gmail.com.

Top 6 Recommended Documents on Financial Modeling

» View more resources Financial Modeling here.

» View the Top 100 Best Practices on Flevy.